On Defense and Unearned Runs: ERA Isn’t the Answer

Last night, Justin Verlander was not at his best, but his overall line looked worse than it was because Torii Hunter made two poor plays in right that cost Verlander two runs, but neither was ruled an error. So Verlander’s ERA goes up because of poor defense even though conventional wisdom is that the “earned” part of ERA factors out your defense making mistakes behind you.

It does and it doesn’t. You don’t get charged for runs that come from errors but you do get penalized when the official scorer makes a mistake (as we saw last night) and when your defensive players do not make a play they should have even though it does not qualify as an error. Sabermetricians have devised other metrics like FIP, xFIP, SIERA, and others to stand in for ERA with a focus on elements of the game that pitchers can control because they have no control of what happens once contact is made. (Read my explanation of FIP for more specific information)

Today, I’d like to offer a little concrete evidence for why ERA doesn’t capture a pitcher’s value. Let’s take an independent measure of defense (Fangraph’s aggregate Fld score) and compare it to the number of unearned runs a team allows (or the percentage of a team’s runs that are unearned).

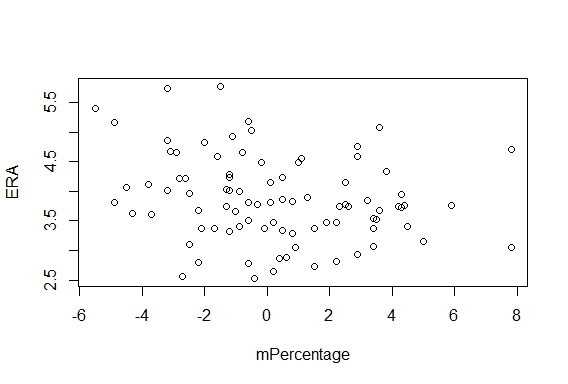

I haven’t looked back into history, but for 2013 the relationship is nonexistent. For the raw number of unearned runs, the results are not statistically significant and are substantively small. On average a team needs to increase its Fld score (range -21 to 18 so far) by about 7 to eliminate a single unearned run on average (range 5 to 25 so far). On average, from worst to first in Fld you can move only 20% of the range of unearned runs. This tells us that the strength of one’s defense does not predict the number of unearned runs allowed. The results are the same if we control for the total number of runs a team has allowed.

Here it is in graphical form:

As you can see, the number of unearned runs has almost no relationship with Fld and if you squint hard enough can only come up with the slightest negative tilt. Basically, what this is showing you is that the difference between your runs allowed and the runs you get shoved into your ERA do not depend on the quality of your defense, it depends on the official scorer and it depends on a lot of other things that have nothing to do with a pitcher’s skill or performance.

This is all by way of saying that ERA is not a good measure of a pitcher’s true skill level. It’s not a bad place to start, but if you look at the Won-Loss Record and ERA, you’re getting very little useful information. Expand your horizon to K/9, BB/9, HR/FB, FIP, xFIP, and other statistics and metrics that enrich the game.

ERA attempts to capture the pitcher’s performance in isolation but it doesn’t. The defense and the official scorer play huge roles in determining that number. If you want to judge a pitcher by themselves, you need to look deeper.

If you’re interested in learning more, I encourage you to visit the Fangraphs Glossary or to post questions in the comment section. I’d be happy to explain or interpret any and all statistics about which you are curious.

The Greg Maddux Way: A Simple Statistic

The great Greg Maddux (355-227, 3.16 ERA, 3.26 FIP, 114.3 WAR) once said the key to pitching is throwing a ball when the batter is swinging and throwing a strike when the batter is taking. That’s a pretty good general rule, but an astute observer would certainly recognize that a pitcher isn’t really equipped to predict such a thing terribly well.

But this did get me thinking, is there something to this idea despite other intervening reasons that confound it? Certainly, if you have a crazy slider that no one can hit, it doesn’t really matter where you throw it. Or a fastball that the hitter can’t handle. It’s also not like where you choose to throw the pitch and if the hitter swings are independent of each other.

So this is an exercise, plain and simple. The Maddux idea is a good one in principle, but it’s not that simple. We know that, he knows that, let’s just look into it for fun.

I drew from the 2012 season and looked at qualified pitchers (n = 88). I developed a simple statistics to quantify how Maddux-y they pitched.

mPercentage = (O-Swing% – League Average O-Swing%) + (-1)*(Z-Swing%-League Average Z-Swing%)

O-Swing% is the percent of the time a pitcher induced the opposing hitter to swing at a pitch he threw outside the zone and Z-Swing% is the same statistic for pitches inside the zone. The -1 is included so that both Maddux attributes are positive and can be added together without converging toward zero.

The results were pretty surprising because some pitchers at the top of the list are awesome and some are average and some are terrible. There isn’t a ton of correlation between this statistic and actual production. The two league leaders in 2012 mPercentage are Joe Blanton and Chris Sale. Cliff Lee is 4th, which sounds right, but Verlander is 42nd.

If you take a wider angle and regress ERA or FIP on mPercentage, you find that on average a 1% increase (i.e. 5% to 6%) decreases your ERA or FIP by 0.06 runs, which is not very much at all. mPercentage is statistically significant in both models, but not substantively significant at all. (The R squared is less than .11 in both.)

So what this tells us is that the Maddux Method doesn’t really exist in practice. Pitchers who induce swings on balls and takes on strikes are no more successful than those who do not. However, there is a obviously a two-way street at play here like I mentioned earlier. The Maddux Method works perfectly in theory, but we have an observation issue given that Justin Verlander’s strikes are much harder to hit than Joe Blanton’s, so he can throw more of them.

I like the Maddux philosophy of pitching, but it isn’t enough. You also need to have good stuff.

Justin Verlander Conquers April (with graphs!)

This particular pitcher, Justin Verlander, is widely considered to be one of the best in baseball. You may disagree with that statement, but he’s certainly one of the very best pitchers in the entire league. Yet he has become the game’s best without doing very well in the season’s first month over the course of his career. Even in his Cy Young/MVP season, his April ERA was 3.64. In 2009, it was 6.75!

It’s been a bit of a thing among Tigers fans that Verlander isn’t that good in April. But he’s getting better and that should probably terrify you if you are a major league hitter.

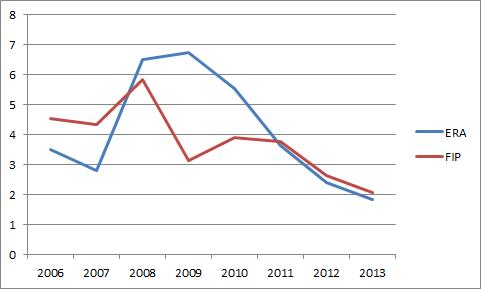

Let’s take a look at his ERA and FIP in April across his career:

There was a time in which Verlander allowed a lot of runs in April and pitched in a way that suggested he would allow runs. ERA tells you what happened, FIP tells you what generally happens to pitchers who pitch a certain way. But over the last few years, he’s conquered April. His 2013 April ERA was 1.83. Imagine what he can do this season now that he isn’t trying to play catch up.

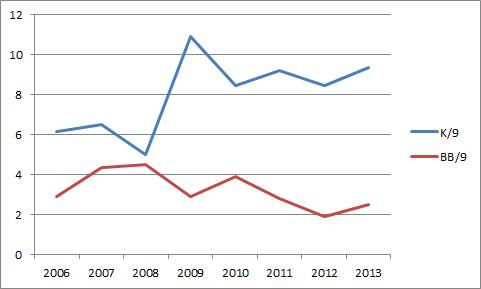

This trend is evident in his K/9 and BB/9 numbers as well:

Verlander has made noticeable improvement in April walk rate over the last few seasons and the strikeout rate hasn’t suffered.

Now maybe Verlander won’t take this great April and turn it into a season better than 2009 or 2011 or 2012, but he very easily could. If he continues his pattern of pitching better in the summer months, then we may be in for a treat. Verlander, I would argue, is nowhere near the top of his game so far this year, but he’s getting good results. When he settles in, it could be awesome.

He’s the richest pitcher in history and his teammates are putting pressure on him to match their great start. Justin Verlander has usually stumbled through April, but he did not do so in 2013. Could this be Verlander’s career year? If April is any indication, clear your calendar for every fifth day and start thinking about a trip to Cooperstown in about 15 years.